The Truth Will Set You Free

The following is the question and answer session following Fr. Carrón’s remarks at the University of Notre Dame, 21 November, 2015.I understand that our problem in the West may be in facing men and women who are afraid of their freedom, or who misunderstand or misuse their freedom. But there is another conflict going on outside of the West, with people who probably don’t disagree with your assertion that freedom does not mean the absence of ties; on the contrary, they believe in community and in serving God in the manner of their understanding. So for this reason I am curious why you discussed together the attacks in Paris and the school shooting in Oregon. The school shooting in Oregon makes sense to me as an act committed by someone afraid of freedom, a life of emptiness. But the attacks in Paris don’t seem to be motivated by the kind of problem with freedom that you’re describing. I’m wondering, then, if you can talk about how that problem fits into this theme as well, if in fact it does. Thank you.

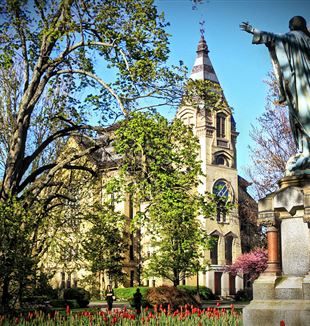

It’s a problem of freedom because of this: the people who arrive in Europe or the United States or wherever, even people corrupted by this kind of radicalism—can they encounter something that challenges their way of thinking? Because that’s how Christianity started. The Roman Empire wasn’t more secure than our own society (we know very well), but Christianity faced this situation and challenged people in their way of life. The question is whether or not we have something to offer: this is the challenge that Christian faith puts in front of us. Are we really convinced that the Christian method, the method chosen by God to save people, His choosing of Abraham—is it a realistic way of changing the world or not? The method decided by God—to become man despite divine power, to be born in a place like Bethlehem, in the condition that we know—is this a realistic way to change the world? Does anybody believe in this kind of design? Because this is a problem of our way of living reality. The challenge is not that the others can do whatever they want, the problem is that we have received something we believe is the truth. But do we really believe this is the answer to all the circumstances in history or not? Or do we believe that this method, God’s design, is too unrealistic? If so, we can close here—and even close the university and the church—and go home peacefully. Because the challenge is not a “kind” of people, but rather our conception of faith. From the beginning until now, when confronted with this kind of situation, what has been the answer of the Christian faith? This is my question. I can understand our surprise, but the radical question is not this one; the radical question is that we have difficulty with the understanding of God’s design, and this is the challenge for us in situations like this.

My question regards the powerful quote about the nature of poverty, humility, and love of enemies, about how we are free through the Beatitudes—quite a departure from the prevailing culture. As students at Notre Dame, graduates, who have growing careers, who need to raise money to build fancy buildings, can you give us some practical advice on how to remain open to that encounter with Christ? How not to get dragged into the affairs of the world which, as you said, are so tempting and so pervasive?

The question for every one of us, whatever the situation, whether we are at war or facing an economic situation—is that we discover something greater than all we have. Because it is not a problem of moralism, of how can we be more poor, or more whatever…as an effort, as something that in the end is impossible for us. The question is whether we can find something so attractive, so beautiful, so fulfilling that we can change our mind. In the Gospel, somebody finds a treasure in the ground and becomes free in their way of using money, power, influence, and relationships—because the question is not that we do not need to have anything, but rather how we can use everything. It’s a new approach—not because I have to gain eternal life, but because I have found now, in the present, something that is greater than whatever I can have, and all the rest is the left-overs in front of the richness of Christ. The challenge for us is: What does Christ mean? Because if Christ is not the most precious thing that we have, then happiness is impossible. A more intense moralism won’t work; we will be defeated in advance because we are incapable of something like that today. The question is whether we live a fullness of the experience of life so that we can be free. Who is able to make us free, fulfilled? Because without this, Christianity is only a more powerful moralism. In the end, moralism is no different than any other human attempt that we know from history. It is the nature of Christianity that is at stake before us.

I very much appreciate, and we all appreciate, the emphasis on community evangelization, and also on personal encounter, personal experience. As a dovetail to the last question, I wonder if you would tell us what are, in your view, the particular challenges for people in the United States—for people in academic professions and for students—in living out the ideal that you sketched.

The question is the same for everybody, whatever their job, whatever their aspirations. I don’t want to say that we don’t need, or we don’t have to pursue, something great or something beautiful; but nothing we can reach is sufficient. The question we need to understand is: What is the nature of our desire? What is the nature of the human being? If we don’t understand this we become, little by little along the way, more and more skeptical that there is no real answer to our desire. We are made with some kind of limit in our nature; we are made in another way. We decide on something that is impossible to achieve, impossible to reach; and it’s true that it’s impossible through our effort, because we are made in this way, with a kind of infinite desire. But in his design, God thinks of us by offering a gift that can fulfill our desire. This is the gift of Christ.

Do you have practical advice?

Only one: in your life, be attentive to finding somebody in whom you recognize this freedom we are talking about. Otherwise, it’s something that we can think of as outside of reality, that what I am telling you is a dream, something that I’ve invented, because you cannot touch it with your hand, you cannot see it in the light. This is the problem of Christianity. It’s an historical event. If you cannot see it in the reality, it’s impossible. Consider the Gospel narrative of the blind man: from the moment he was born, it was impossible for him to imagine that in his society it could happen, something like the miracle of encountering a man who could cure him of this illness. It was something impossible for him to imagine before it actually happened. He woke up that morning expecting some coins from people who passed on the street; the only thing that was impossible for him to imagine was that somebody would pass by and cure his illness. It was impossible. What counsel, what advice could you have offered him beforehand? Only somebody who has experienced this kind of change can say to you, “If I were you, I would be attentive to somebody who is called Jesus Christ, because he’s useful for you if you want to be cured.” But for many people something like this is unbelievable. It’s not that you need to stop, study, and wait; rather, you keep studying and open your eyes because it’s something that is in reality, and many times we are so busy with other things that we cannot realize what is in front of us.

Thank you, Father, for your presentation, and for bringing up the story of the pearl we sell everything to pursue. I want to connect that story to what you said earlier, the quote from Fr. Giussani about freedom “on the way.” I really like that, but it seems to me that in interacting with people of different beliefs, other Christians or secular people, or lapsed Catholics, there is some kind of tension between the experience of going out and the necessity to create freedom “on the way,” especially when these people are not always able to articulate their beliefs and their emotions, or the way Catholicism manifests itself to them. Can you please comment on that?

You can imagine that God decided to come here to help people be free, to appear in the history of Jesus. How can He do that? How can He put somebody, some presence, some way of living life in front of people, in such a way that people can come, can meet him, can experience this kind of freedom? All the narratives of the Gospel are cases of this kind: people like Zacchaeus, or Matthew, or the Samaritan woman, or John and Andrew, who met Jesus and experienced a kind of fulfillment that was impossible for them to imagine beforehand. Christianity is impossible to invent; after ten years not even we can imagine the things that the Gospel tells us, even if we are used to listening to this narrative. Imagine the time before somebody wrote this narrative. It was impossible even to imagine; it’s an event. A real event that nobody could imagine before it happened. For this reason, it’s the same here, now, there is no difference. We think we know what Christianity is about, and many people around us can imagine this, but we ask questions like, “Is it still possible, after 2000 years? This is the question: What is Christianity? Only if this encounter happens today can we really look at the Gospel as real, not as an un-real narrative, something invented. This is the challenge we have. St. Paul could go all around the Roman Empire with the conviction that Who he met on the journey to Damascus could be the answer to all of the desires of men and women in that time. Only if we experience this can we offer it to others along the way, wherever and whatever the circumstances. Christianity was communicated through slaves, through merchants, through traders; normal people without any kind of strategy, only communicating this newness. It was the same as in the beginning. Today, this is very important, as we are in the same situation as in the beginning. We are in a pluralistic environment, which is ever more pluralistic, and so the question is whether or not we have something different than all of the other opinions, that can be offered to those who are in search of the freedom we have received as a gift.

Thank you very much.